Galaxy formation is a paradigm that has shifted over the years from being something that scientists did not understand at all to becoming a well-tested theory with a basic understanding.

Dr. Kyle Stewart, assistant professor of physics at California Baptist University, with a team of other scientists, authored papers in 2011 and 2013 that theorized the current idea of galaxy formation, running simulations to support their ideas. As of last month, a group of California Institute of Technology astronomers validated this theory, thus confirming it within the scientific world.

“It’s really cool,” Stewart said. “Usually you make some wild theoretical prediction and it’s years before they tell you that you’re wrong, or every once in awhile they tell you that you’re right.”

Ten years ago, the basic idea surrounding galaxy formation was that the gas used to form a galaxy was flowing in from all different directions. Gravity attracted the gas to denser regions, making it more difficult to observe and confirm that this was how it was happening.

Stewart was in graduate school at the University of California, Irvine, when the paradigm of galaxy formation began to shift. As a result, galaxy formation began his topic of choice to study.

“When I had to pick an actual topic to do research in graduate school, I immediately started with galaxy formation,” Stewart said.

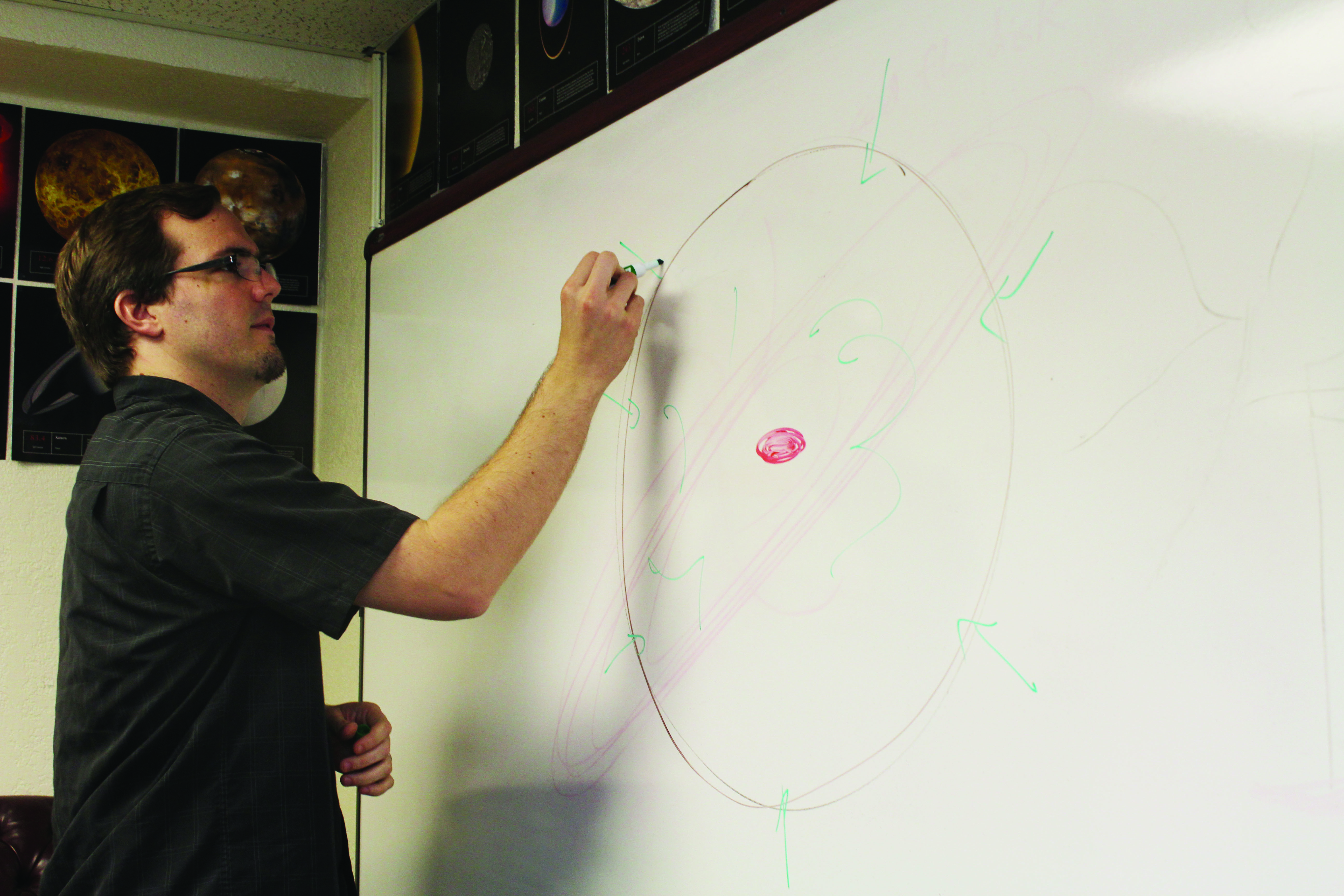

In 2009, he began to run simulations on a new postulation. This theory changed the face of galaxy formation. He and the team he was working with called it a rotating cold-flow disk.

The idea is that gas, rather than entering galaxies randomly, is flowing in at preferential directions. The overshooting angles of the gas, added to gravity that pulled it around as it entered, causes a huge rotating disk to form that is three or four times bigger than the actual galaxy. Not as much heat is produced as scientists thought before in the process, so the term “rotating cold-flow disk” was coined.

The group of astronomers from Caltech ran a simulation last month in which they were able to view one of these disks, thus confirming the theory.

“It’s a very fun field to be in because clearly the simulations are doing something right,” Stewart said. “To be able to simulate the development and growth of a galaxy from its first stars to what we might see today is very cool, but at the same time, there’s a lot of stuff that we don’t know the details.”

According to Stewart, the next step is to look at various simulation codes that other people have used to confirm that everyone is reaching the same end result and that the theory agrees with itself.

Stewart says that the validation of his theory is exciting, not only because of the scientific advancement, but also because of the subtle reward that it implies.

“If you make some predication that turns out to be true, people will start referencing your work, and in the scientific field, the number of people who reference papers that you’ve written is kind of a metric for how good your science is,” he said.

As for some of who Stewart works with at CBU, the success is equally as exciting.

“I am very happy for him because he is still young in his career, so to get something so prestigious at such a young age is exciting for him career-wise,” said Lisa Hernández, associate professor of mathematics and chair of the Department of Natural and Mathematical Sciences. “It’s really good for the promotion of physics at CBU.”